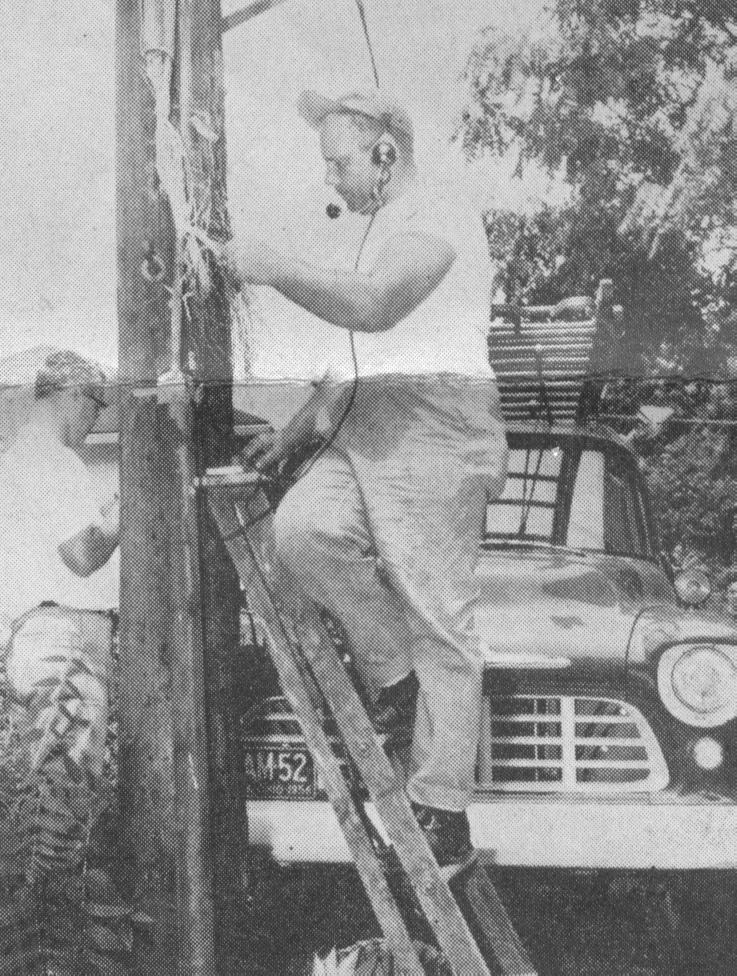

Firemen arrived too late to save the house of Robert Nutter (right) and his aged parents near Portsmouth. Their telephone was dead because of the labor-management battle in the Ohio Consolidated Telephone Company.

She padded downstairs to the telephone. "Police," she whispered even as she dialed. But there was no dial tone; the line was out.

For a moment she slumped down against the wall, holding the dead phone against her side. Then she walked slowly to the front door and snapped on the porch light. Waiting there, her finger still on the switch, she heard the sudden silence at the back door, and then the soft tread of retreating feet.

Minutes later, she crept into the kitchen, flicked the switch of the porch light, then tested the door. It was still locked. She dropped into a kitchen chair and waited for dawn. It was 1:30 a.m., October 16, 1956, in Portsmouth, Ohio.

A mile away at Smith-Evertt Hospital, a 71-year-old man died in his sleep. A nurse pulled a sheet over his face and went to notify his relatives. But the telephone was out of order. Relatives were informed twelve hours later.

This was the morning that every telephone in Scioto County, Ohio, went

silent. For 61 consecutive days 17,428 telephones did not ring, and

approximately 110,000 persons in Southern Ohio and Northern Kentucky could

not telephone for a doctor, a policeman or a fireman. For two months

they were desperately, sometimes frantically, without a service that most

Americans take for granted.